Regardless of how many times I practice a speech – or how many times my extremely patient friends listen to me practice a speech – I never feel quite prepared to step in front of a crowd. So, presenting about my Ph.D. research would have been nerve-wracking enough, but explaining how I’m using mini-brains to model traumatic brain injury at the United Nations Headquarters was both intimidating and exhilarating.

I was one of two Brown University graduate students selected to participate in the first Ivy 3-Minute Thesis (3MT) Competition at the United Nations on April 25. But, let’s back up for a second. What’s a mini-brain, and why would anyone want to use them to model brain injury?

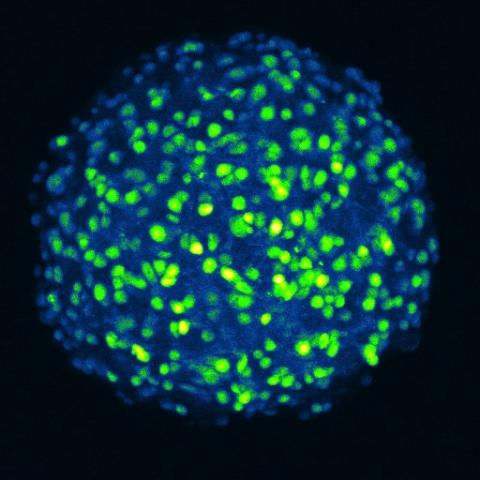

Scientists have been culturing neurons on petri dishes for decades. However, the cells in your brain don’t normally live on a hard, flat surface, and growing them that way can affect how they behave. Recently, researchers have begun culturing brain cells (both human stem cells and primary rodent neural cells) in three-dimensional spheres. Neurons and glia in these mini-brains take on shapes that are much closer to our brains than that of two-dimensional cultures.

In the Hoffman-Kim Lab, we went so far as to show that the cell density and tissue stiffness were also comparable to what’s found in the brain. We can make hundreds of mini-brains, and we still have precise control over their environment. These features – of reproducibility, fidelity, and control – make mini-brains a very attractive target for drug development, toxicity screening, and disease and injury modeling “in a dish.”

One of the things that makes the brain so interesting is that the activity of the neurons is just as important as their shape. Neurons fire electric pulses at one another, and these electric pulses form the basis of how we process information every day. A group of neurons might look fine, but if they aren’t communicating properly, devastating cognitive issues can result.

As a Ph.D. student in neuroscience, I’m studying network behavior in mini-brains, and I’m looking into how those networks are changed in injured or pathological states. Normally, networks in a mini-brain develop in a predictable manner. Neurons form connections, exhibit some pretty synchronized activity, and then develop into a system that’s still coordinated, but has more complex harmonics.

Right now, we’re creating mini-brain models of traumatic brain injury, as well as ischemic stroke and neurotoxicity. Some of the questions we’re asking have to do with whether the cells look different after injury, but I’m interested in looking at changes in activity to see if they can tell us how damaged a spheroid is. You learn more when you can see a neuron’s activity patterns in addition to its shape.

From the bench to the podium

I’m also passionate about science communication – I believe the onus is on researchers to explain our science in a way that others can understand and care about, whether we’re talking to other scientists, funding agencies, or to laypeople. This year, I was selected to participate in Research Matters, an annual event at Brown that challenges graduate students to explain the importance of their research in five minutes or less. I was excited to have a chance to show the broader community how cool my science is in a short and approachable format.