In 1979, Brown launched Neuro 001, one of the first undergraduate neuroscience courses in America. Faculty lecturers from physics, psychology, medicine and biology taught the course and used a rich, unruly array of science papers, book excerpts, and typed notes that, together, served as the collective course materials.

There was no textbook to guide faculty or students. Neuroscience was too new. (The Society for Neuroscience was just 10 years old in 1979). When Neuro 001 was launched, all that was known about the brain and nervous system was stitched together from psychology, biology, anatomy, physiology, chemistry and physics. Neuroscience by its nature is interdisciplinary, and no one had yet brought discipline to all the knowledge that converged to create it.

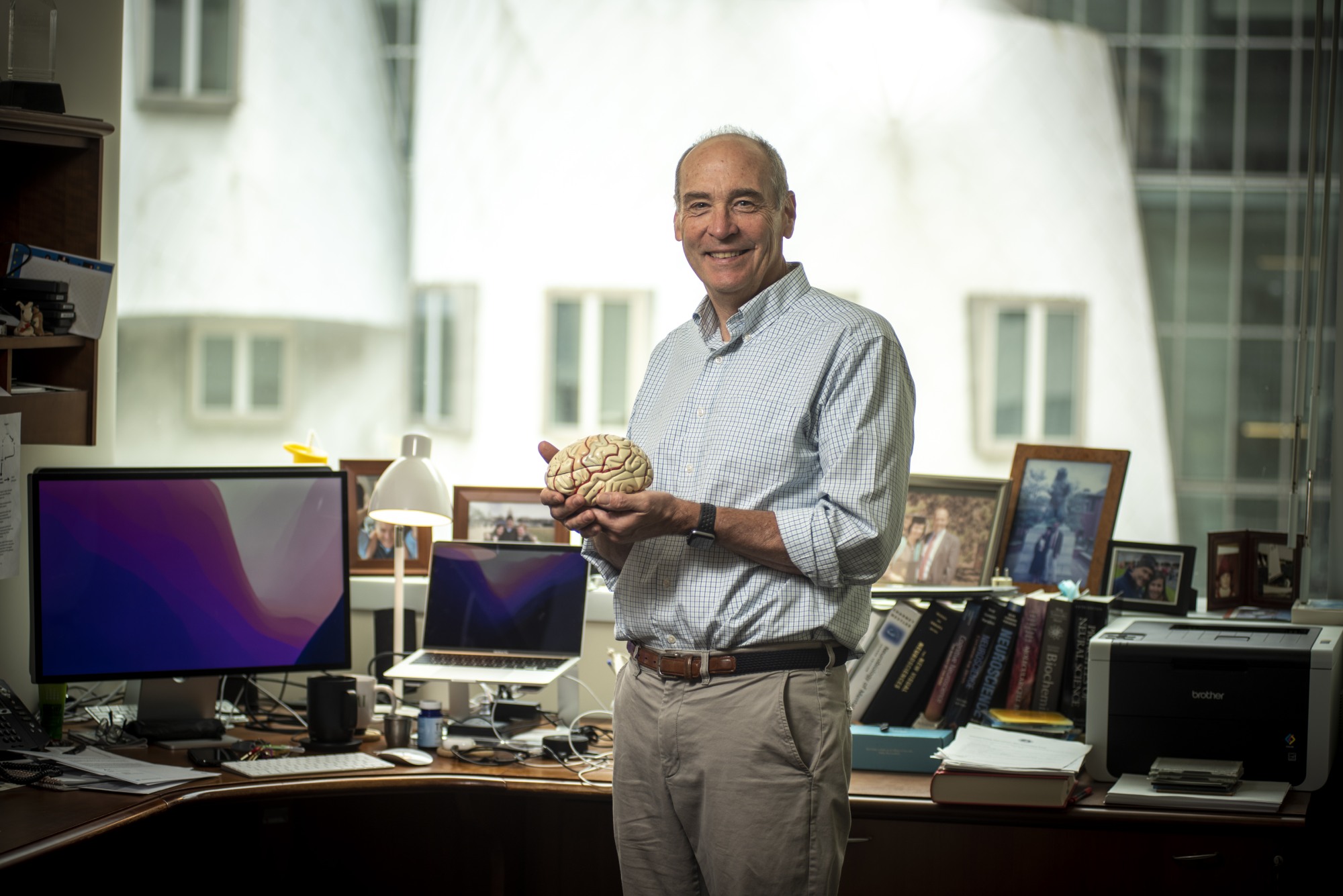

Mark Bear took over Neuro 001 in 1986. After years of managing mountains of paper course packets, Bear knew it was time for a textbook – and an editor approached him one day in the halls of the medical school and urged him to write it. Eventually, Bear asked two Brown colleagues, neurobiologist Barry Connors and physicist Mike Paradiso. Did they want to write the book on neuroscience?

They agreed. The result is “Neuroscience: Exploring the Brain,” the first introductory college neuroscience textbook, which this year celebrates its 30th anniversary. Bear, Connors and Paradiso just put the finishing touches on the fifth edition, to be released this spring. Through its 1,000-plus pages, these brain scientists have taught a generation, shaped careers and college programs, and traced the arc of progress in the field.

Their book is also a driver of global impact for Brown and its Robert J. and Nancy D. Carney Institute for Brain Science. Since it hit classrooms in 1995, “Neuroscience: Exploring the Brain” has gone on to become the world’s most widely used neuroscience textbook. According to publisher Jones & Barlett Learning, the textbook has been translated into French, Spanish, German, Portuguese, Italian, Japanese and Chinese and ordered for use on six continents. Besides North America, it’s particularly popular in Brazil, Australia and the Middle East, they report, and over 400 American colleges and universities have used it. Students at Cornell and Columbia, Boston College and Brigham Young University, Tulane and University of Texas have studied from its pages.

“This is a great example of the ingenuity of brain scientists at Brown,” said Diane Lipscombe, Reliance Dhirubhai Ambani Director of the Carney Institute. “Whether it’s textbooks for students or tools for scientists, our researchers create what’s needed to drive discovery.”

For the authors, the book is a lift and a gift.

Generating the first edition took hundreds of hours of research on topics ranging from the biology of the neuron to the anatomy of the nervous system, from sensing and moving to thinking and behaving. The authors knew the book must be engaging and accessible, something that any undergrad with some high school science could understand. That’s why they asked for full color printing – a big risk back then for textbook publishers – and used hundreds of photos, illustrations, and graphics. Bear, Connors and Paradiso also solicit first-hand stories of big discoveries directly from brain science giants like Eric Kandel, Solomon Snyder, David Hubel, and Edvard and May-Britt Moser.

To write five editions, Bear, Connors and Paradiso stretched their own brains, staying on top of the latest neuroscience advances in order to integrate and explain them to students. All the progress of the last 30 years – the sequencing of the human genome, the invention of functional magnetic resonance imaging, the rise of neurotechnology, the discovery of new families of brain cells, fresh insights into brain disorders – had to be digested, distilled, and passed onto the page.

But the stubborn mysteries, rather than the dramatic discoveries, most surprise the authors.

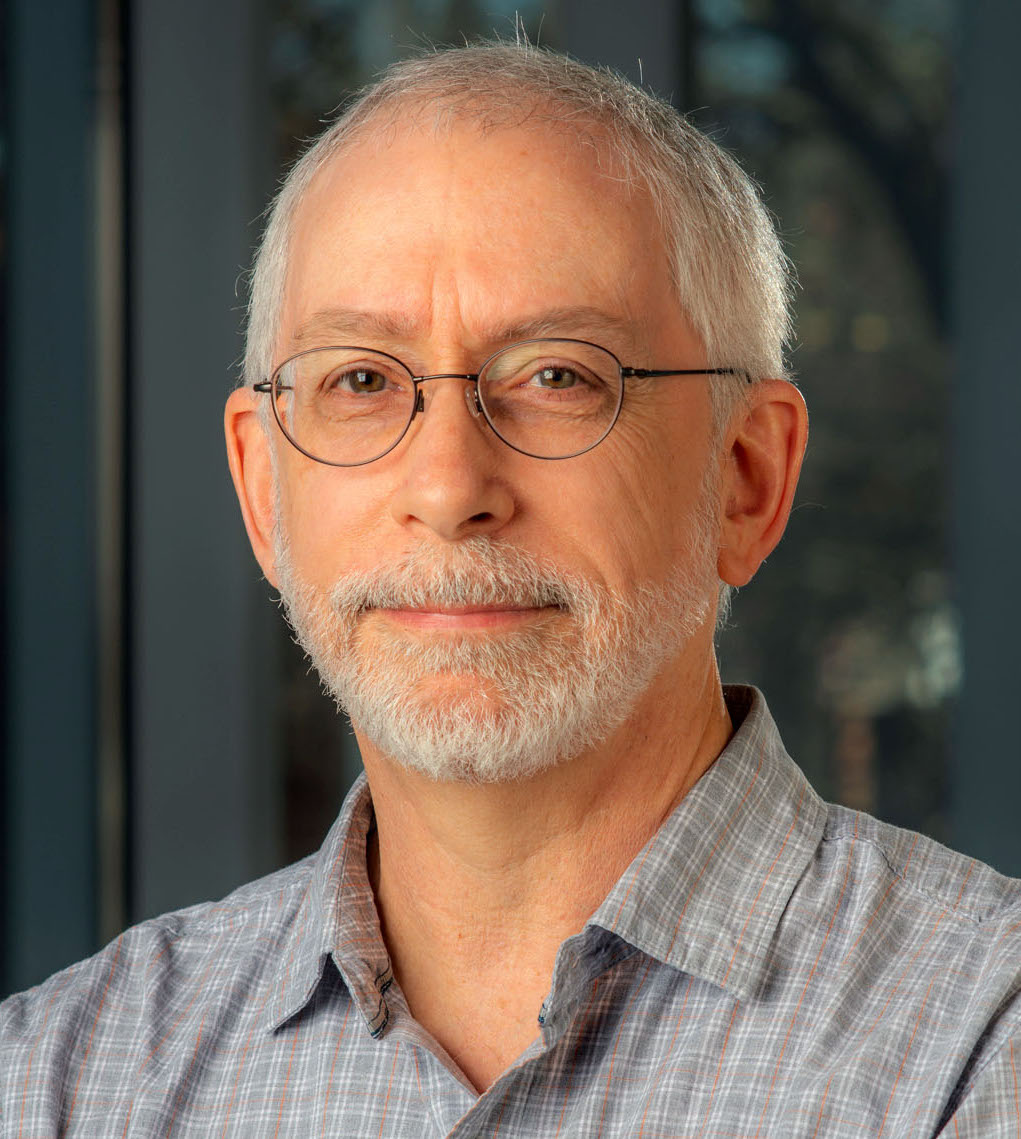

“It’s shocking how little we still know about diseases like Alzheimer’s,” said Paradiso, a professor of neuroscience and the Sidney A. Fox and Dorothea Doctors Fox Professor of Ophthalmology and Visual Science. “We’ve seen incredible progress in neuroscience, but there’s still so much we don’t know. That’s part of its appeal.”

Working on the books has benefits. Royalties helped the authors put their kids through college, and they’ve even been treated as stars, with undergrads asking them to autograph t-shirts, conference badges, and, of course, their books. Bear was rushed by Brazilian undergrads after receiving an award in Rio de Janeiro. The work birthed some great stories, like the daughter of a Hollywood star who so despised Neuro 001, she torched the text in a public display in a Brown parking lot.

“Neuroscience: Exploring the Brain” has also fed the field. Colleagues from across the country have reached out to the authors to get advice on starting a neuroscience course or, in the case of schools like Georgia Tech, to create an undergraduate concentration.

“We’ve all heard, many times, from students who said they had no interest in science until they took Neuro 001,” said Connors, L. Herbert Ballou University Professor Emeritus of Neuroscience. “It’s been a feeder course for people to discover and join the field.”

The popularity of Neuro 001 remains strong, with about 300 students enrolling each time it’s offered. An estimated one in four Brown students take the course, which is led by Paradiso. When Bear left Brown for MIT in 2003, he started an introductory neuroscience class there.

“We’re the leading undergraduate textbook and have been around more than a quarter century,” said Bear, Picower Professor of Neuroscience at MIT. “That’s allowed us to introduce neuroscience to a new wave of students and given others basic science literacy. I’d like to believe we’ve had a big impact.”