A new study revealed that certain brain regions are more active in people with obsessive compulsive disorder during cognitively demanding tasks. The findings could help inform new possibilities for how the condition is treated and assessed.

The study was published in Imaging Neuroscience by researchers in the lab of Theresa Desrochers, Rosenberg Family Associate Professor of Brain Science at the Carney Institute and professor of neuroscience.

Desrochers studies abstract sequential behavior––behavior that follows a general sequence even though individual steps may vary, such as getting dressed in the morning. Researchers had not previously examined potential links between abstract sequencing and OCD, a psychiatric condition characterized by repetitive thoughts or actions that cause distress for the individual.

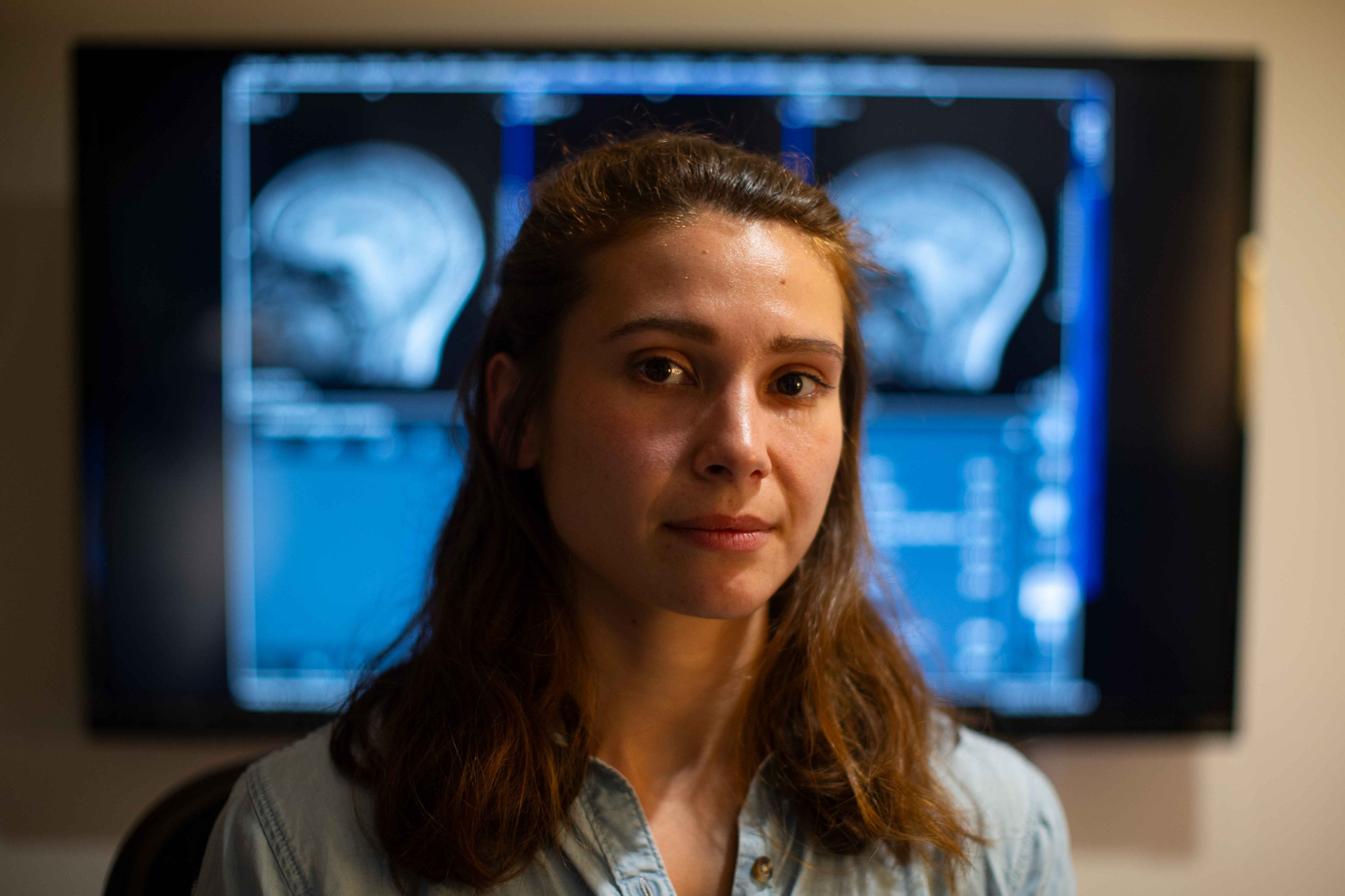

“We started looking into OCD because symptoms of the condition suggest that patients lose track, or get stuck where they are, while performing sequences,” said lead study author Hannah Doyle.

The study team asked participants to perform a sequential task in which they named the color or shape of an object in a specific order. Doyle found that while individuals with OCD were able to perform the sequence as well as the control group, the MRI imaging revealed differences in regions connected to motor and cognitive task control, working memory and object recognition. “Their behavior looked similar, but the brains of the participants with OCD recruited more brain regions than the controls.”

Some of these regions haven’t been specifically linked to OCD before, said Doyle. Those regions include the middle temporal gyrus--involved in working memory, semantic memory retrieval, and language processing--and an area spanning part of the occipital gyrus and the temporo-occipital junction, which is involved in lower level visual stimulus processing and object recognition.

Nicole McLaughlin, an author on the paper and a neuropsychologist at Butler Hospital, said the findings may lead to new TMS treatment targets for OCD. TMS, or transcranial magnetic stimulation, is a therapy that uses magnetic pulses to stimulate brain regions implicated in a psychiatric disorder. TMS was approved as a treatment for OCD by the FDA in 2018; research has shown improvement in about 30 to 40 percent of OCD patients.

The treatment might be even more effective if these newly implicated regions are targeted, McLaughlin said. “If we reposition coils during TMS treatments to be near these regions, we might end up seeing a greater improvement in symptoms.”

The real-life relevance of the study task was likely key to the team’s insights.

“A lot of neuropsychological tasks exist in the context of a single static decision that you have to make,” said Desrochers, who first developed the task with David Badre, professor of cognitive and psychological sciences at Brown. “But as humans, we interact with the world through time and through sequences, with larger goals that have smaller decisions beneath them.”

The sequencing task calls for participants to name the colors or shapes of a series of images in a particular order, such as color, color, shape, shape –– requiring the ability to keep track of a sequence while making a categorization decision. “This task gets us closer to understanding what actually looks different for folks with OCD when all of these different cognitive control systems are trying to work together,” said Desrochers.

McLaughlin added that the sequence task itself could also be used as a new assessment tool. “We are planning to use the task in between treatments,” she said. “If we start to see OCD patients’ brains looking more like control participants when they perform the task, that could help indicate that TMS treatment may be effective for symptom reduction.”

FUNDING INFORMATION: This work was supported by a 2020 Seed Grant from the Office of Vice President for Research at Brown University and the National Institute of Mental Health (R01MH131615). Hannah Doyle was supported by a 2024-2025 Graduate Award in Brain Science from the Carney Institute (the Dr. Daniel C. Cooper Graduate Award and the Howard Reisman '76 Family Graduate Fellowship Fund) and the Training Program for Interactionist Cognitive Neuroscience (ICoN; T32MH115895). Research was in part supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (P20GM130452).